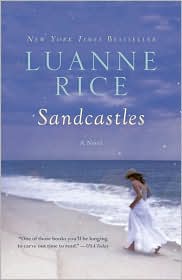

Written on a random flight, who knows when, on one book tour or another.

up in the sky

by Luanne Rice

when i fly, i go up in the sky.

it's true, and i'm up here now.

all around me is blue, except for long cloud highways leading to and from canada and other places. below me, there is haze. through it i can see rivers, ponds, towns, hills, roads. i am in a dream.

in the dream i join a parade of people, strangers, pulling suitcases on wheels, bumping along the jetway and over the narrow space between it and the jet door, and onto this large conveyance. it is a jet plane. i almost never dream of parades. and as a waking hermit, i rarely, well, never, march in them--but that's not even the strange part. the surreal part of this dream is taking off from the ground, going up into the sky, in a flying machine. this is not my natural element.

i did not always feel this way.

when i was young, i was as one with the sky. i flew with abandon. i'd go flying with my cousin--a true beach boy with whom i used to go crabbing at the rocky end of the half-moon beach known as hubbard's point, an experience about which i wrote my very first published story. his name is tom. when tom was 16, even before he could drive, he got his pilot's license. he wanted to get as many flight hours as possible, and i was right there beside him. we flew everywhere. we buzzed his teacher's house in harwinton. we flew home from the airstrip near waitsfield, vermont in a snowstorm.

we used to charter an old seaplane. he would land in the boats-only area right by the crabbing rocks at the end of the beach, to pick me up. i'd swim out to the plane and climb onto the pontoon and into the cockpit. my seat would be soaked with salt water. he'd turn us out to sea, and we'd bounce over the waves. the plane was so old that when he took off and banked right, the passenger door would flap open and i'd be looking straight down at long island sound.

fearless children we were.

then there were the paris years. i lived in paris with my first husband. his name was also tom. we were young and in love. with each other, with everything. every day i would walk along the seine for hours, trying to memorize the exercises my tutor, madame piochelle, had given me. "allo, allo, ici george, qui est la?" "c'est moi, jean!" "vien jouer avec moi?" "oui, j'arrive." "a tout a l'heure." "a tout a l'heure." i would also shop at the marches, especially rue cler, for our dinner. once i bought a whole rabbit. i don't remember how i cooked it, but i do know that i have bad dreams about it now. tom loved my cooking, and i loved doing it for him. to me, that was the essence of love.

once on the terrace of chez francois, near the pont de l'alma, i met bono. actually he said his name was paul , I didn’t figure out he was bono until a bit later. this was just before joshua tree. we started talking--about love, being irish, being american, being writers, and love again. what else was there but love? nothing.

during that time, my mother developed a brain tumor. i flew home a lot, to see her. that was the first time i remember feeling skeptical of flying. would the plane get airborne? would it actually land? maybe i was really afraid of something else, like losing her. i'm not sure. but the way i got myself through those feelings was to think of my father, who had been in the air force.

his name was tom, too.

world war ll, he was stationed at a base at north pickenham on the wash, north of london. he was only 23. he trained for a year in colorado springs. before that, he'd never been in a plane. he grew so close to his crew--as close as brothers. he was navigator-bombardier. once in england, flying missions over france and germany, he stood out and was promoted to the lead plane in the eighth air force. he refused to leave his old crew--his new crew had to literally carry him and his possessions to their nissan hut. the very next mission, his old crew was shot down over helgoland.

that's not the part that inspired me, exactly. although writing it, i see that it sort of did. somehow my father kept going. i can only imagine his grief. he flew on d-day, over normandy. his was the first plane over dresden, shot down on his way home. he was irish-catholic. i think of him, a beloved and sheltered boy from a close hartford family, thrown into war. he had a very sensitive soul.

promoted to the lead plane in the 8th air force, he was the very first plane over Dresden. on his way back from that dreadful bomb run he was shot down. other planes, his friends, went down in flames all around him. he parachuted out, crash-landed in a tree in occupied france and broke his back. he was rescued by a family with three daughters; they hid him in their barn. after he got home and married my mother, they had three daughters. my sister rosemary also has three daughters.

cosmic, non?

bien sur.

during my paris flying years, i would quell doubt and fear by thinking of all the times my father flew without getting shot down. over 25 missions. back and forth over the english channel, during tempests of all kinds. wild winds blew, making the plane shake. they would lose altitude, but just keep going. i imagined his old bomber, strafed with shrapnel, taking off and landing again and again.

there i was on the concorde--who was i to worry? i was really just a spoiled traveler. anyway, my mother wound up coming to paris to have her chemo at the american hospital. i didn't fly as much after that. although tom took me to venice for my 30th birthday. we stayed in a sweet hotel behind la fenice.

i heard placido domingo singing in the courtyard.

one night tom and i took a water taxi to the lido. i had to put my feet in the sand and feel the salt of a brand new, to me, sea. i thought of thomas mann. there are times when i'm an existential beach girl. but i guess if you're reading this, you know that by now.

the next time i felt tense about flying was many years later.

fast forward.

through life, life, life.

many beaches later. mistakes, mysteries, flights and passions later.

marriages, too.

okay, here's the story. i was on book tour in summer, 2001. trans-canada, from fredericton to vancouver. at the time, i was in the midst of a tragic, unbecoming, and completely abusive non-love situation. my third marriage. snares had risen from the depths, wrapped themselves around my ankles. that made it hard to fly. how can you rise--above the earth, above anything--if you are tethered from below?

my itinerary took me amazing places. halifax, toronto, calgary, banff, lake louise. being so far away and so often up in the air let me see my life with some persective.

look down through the clouds and see what is.

that book tour saved my life. it showed me my strength, and that I didn’t have to stay with him. kick him out, reclaim myself. surround myself with real love—not twisted, psycho control masquerading as a marriage. I was out of there.

thank you, sky, for holding me aloft.

thank you, plane, for taking me away.

thank you, my own strong heart, for never giving up.

i know i can fly because guess what? i’m doing it right now.

still, it's a dream.