Winter Institute is amazing and what a joy it was to spend time with independent booksellers. I was invited by my wonderful publisher, Scholastic (book fairs! book clubs! Harry Potter! The Hunger Games!) to join the party in Denver CO and talk about my first YA novel, The Secret Language of Sisters. My fellow authors were Sharon Robinson (great writer, daughter of Jackie, my mother's idol) and Derek Anderson (amazing artist and writer of picture books) and we celebrated the fact that writing for children (in my case teenagers) is a very special calling. Their warmth and welcome into this new world for me made me feel so lucky. On top of that, we were taken care of, introduced, and nurtured by Scholastic's inimitable Bess Braswell and Jennifer Abbots.

Read MoreNorthern Light

It was winter, but I went north. I wanted the deep and dark, and I dreamed of seeing the aurora borealis. Living in New York City, I follow an aurora forecast on Twitter, and a blog about a Baffin Island expedition. One Christmas I came close to booking flights to Iqualuit--it would have taken twenty-four hours to get there--because I longed for the polar dark. I've held on to that desire for some time. My friend Bill Pullman was playing Othello at Den Nationale Scene in Bergen, Norway. So although I had been a serious hermit for a few weeks, writing and not leaving the apartment, on February 16th I flew over to see the play. Bill is brilliant in it, uncovering dangerous truths about jealousy and solitude, and the way a specific kind of aloneness can make a person go mad. Othello's undoing and explosion are exquisitely drawn. The play is directed by Stein Winge. It is one of Bill's great performances.

I explored Bergen, the waterfront, and the National Theater itself. Ole Friele, Information Manager, arranged a backstage tour. Henrik Ibsen had once been writer-in-residence, and the theater is full of history and magic, with a gilded lobby ceiling and carved boxes.

Later Gunnar Staalesen, a lifelong resident and author of mysteries set in Bergen, gave us--Kathryn and Sam, two other friends of Bill's, had also flown in from New York--a tour of town. We walked the Bryggen quay lined with colorful wooden buildings, past the 12th century St. Mary's Church, out to the 13th century stone Bergenhus fortress near the harbor's entrance. There is nothing like being shown Bergen by one of the fathers of Nordic Noir.

A steady rain began to fall. Gunnar spoke about how the town had survived layers of war and fire, and how during World War II it had been occupied by Germans and bombed by Allied aircraft. Visiting Europe always makes me look up at the sky, where my father flew a B-24 on thirty bombing missions--Bergen was not one of them. I think about him, and how he was only twenty-three years old, and about the people on the ground, and all the ones who died. There is a kind of sorrow to these visits, solemn and graceful.

I had planned on flying straight back to New York, but during the walk to the fortress I saw a Hurtigruten ferry in the harbor, and everything changed. The ships ply the fjords in a northerly route along Norway's west coast, from Bergen to Kirkenes, transporting cars, cargo, and passengers. This might be my chance to go far-north. I called on the off-chance and snagged the last cabin on the next ferry.

It was literally the last cabin--a small single all the way aft on the starboard side of Deck 6 of the MS Finnmarken--and it would be mine as far as Tromsø. We steamed out of Bergen that night, up Norway's jagged west coast in mostly calm seas. I was stunned and transfixed by the light: the silhouette of fjord walls in daylight, stark against the sky, and at night, blocking out great black patches among blazing stars.

At night we passed tiny towns nestled in natural harbors and single houses perched on cliffs, lamps glowing warmly in the wilderness. I watched until they were out of sight, and I wondered about the people inside. Were they happy? Were they lonely, or did their inner lives and the fact of being surrounded by spectacular natural beauty provide enough solace? Did every lighted window represent someone on the Internet? Is there a place on earth to find contentment, or do people everywhere imagine peace, love, and understanding to be greater anywhere but at home? I wanted to believe in their coziness.

Late one night we pulled into Kristiansund. A woman's voice came over the loudspeaker, animated and proud, telling about the heritage of the port, how it was known for dried and salted cod, that no place in Norway had produced more. She said the ship would be docked for about thirty minutes, and if we wanted we could walk to the square to see the sculpture of the "fish girl." It was midnight, and I was in my bunk. But the emotion in the speaker's voice made me get up, and I left the ship. The statue was a few wharves away. The bronze woman stands tall and proud, holding a slab of dried cod.

I found it so moving. The fishing industry is full of danger and hardship, economic uncertainty, and deep family connections to a way of life that depends on nature. Traditionally the fish haul was prepared and spread on the rock cliffs, to be dried by wind coming off the sea, and women and children tended the klippfish drying process. The fish girl worked hard, I had no doubt.

We crossed the Arctic Circle at latitude N66.33 one night. The captain told us what time to look off the starboard side. I climbed out of my bunk and saw as we passed the Arctic Circle Monument, an illuminated tilting silver globe standing on a promontory. I felt I had arrived at something, a place I had needed to be for a long time.

The feeling continued. I was in the Arctic. This was a strange emotional homecoming to a place I'd never been. I watched the landscape grow even more austere and dramatic. I scanned for whales, but was told it was the wrong time of year, they had migrated to other feeding grounds. Around Trollfjord we passed a Snowy Owl resting on a ledge, and I saw many raptors including White-tailed Eagles, also known as Sea Eagles, circling bays and mountaintops.

My reading has long taken me north. Salamina by Rockwell Kent; fiction and essays by Joe Monninger; Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez; This Cold Heaven and The Future of Ice by Gretel Ehrlich; The View From Lazy Point by Carl Safina (especially the arctic sections); and Great Heart: the History of a Labrador Adventure by James West Davidson, are some favorites, but there are many more. To actually be so far north during February, observing the landscape I had only dreamed about, eased my heart.

The planet seems less fragile there. That's an illusion, of course. The ice caps are melting, species are endangered, overfishing is a reality, and birds are losing habitat all along their migratory paths. But to see so much empty space, open ocean and uninhabited land, gave me hope that there are still some places that humans haven't totally ruined by imposing themselves everywhere and maybe won't. Then we passed an oil rig.

Being on the ferry reminds me of hibernation, a waking dream. Everything is so beautiful and extreme out there, beyond the ship's rails. Most days were cloudy, but even on the bright days the February light was muted somehow, it didn't assault the eyes and spirit, it didn't demand that a person's mood match it. The Arctic felt safe and comforting to me, as I somehow knew it would.

That is not to say that depression drives a love of the north. But depression is an edge, and so is the Arctic, of an internal landscape and of a continent. The north is remote and rugged, and the difficulties of living there are epic. Light during the winter months is clear and rare. A person who is depressed has a similar complicated relationship with light: you know you should seek it, and you sometimes feel grateful to it when you do. But the instinct is to hide from it, to find comfort and stillness by going inward.

One night, my last on the ship, I saw the aurora borealis. It might have been my first time, although I am not 100% sure. Once in about 1989, in the Old Black Point section of Niantic, Connecticut, I saw what I swore was an aurora. My sister Maureen remembers me calling to tell her to look northwest. We saw something bright and unusual and lasting in the sky, but to this day I'm not sure. And it looked very different from what I saw from the deck of the Finnmarken.

We had had just left the town of Stamsund heading north through the fjord when the captain announced there was an aurora dead ahead. He turned off the deck lights, and the night was very dark, cold, and crystal clear as we gathered at the rail. There was no moon.

The aurora began as a white band, an elongated half-oval similar to mist, ghostly but with a distinct curve just above the horizon. Within moments it had spread high and wide, above the low mountains off the port side, colors ranging from pale to bright green in organ pipe-like spikes, in parts swirling blue and pink. Over a period of thirty minutes it morphed into different patterns while maintaining the ghost of the original oval. The Big Dipper was just overhead, the handle arcing towards the port horizon, with Arcturus deep in the shimmering lights.

Throughout the night we passed through narrow straits lined with towering mountains, and the aurora came and went. At times it seemed to surround the ship. The stars were so bright behind green fire. Orion walked through it, balanced on the horizon. I stayed on deck for a long time. My hands were cold and numb, but I kept watching.

The next day we docked in Tromsø. I nearly asked if there had been any cancellations, if I could stay in my cabin and just keep going north. This might sound strange, but after the experience of the night before, seeing the northern lights, I didn't want to keep chasing them. I felt I had gotten more than I'd dreamed of--to see them above the cliffs of the fjords on a totally moonless night, with all the constellations in the background. Even now I can't explain how meaningful the light, and the dark (especially the dark--so blue and beautiful) was to me. The north in winter is a nocturne, a luminist painting.

After I got off the ship, I flew to Oslo. I had seen my friend play Othello, and I'd finally made it to the Arctic, and I'd seen the northern lights. I had every intention of returning straight to New York, but there in the Oslo airport I realized I wasn't quite ready to go home. So I hopped a flight to Paris instead.

Photos of Norway, all taken on my iPhone:

A chance to meet with writing students...

Speaking to students is one of my favorite things to do. There is something about meeting young writers, full of hope and ideas, and letting them know I believe in them, I know they can do it if they really want to. That seems to me to be the most important factor: desire. The desire to write, to express what's inside, to complete a work of fiction or non-fiction, to want it so badly you won't give up on yourself or the work.

Speaking to students is one of my favorite things to do. There is something about meeting young writers, full of hope and ideas, and letting them know I believe in them, I know they can do it if they really want to. That seems to me to be the most important factor: desire. The desire to write, to express what's inside, to complete a work of fiction or non-fiction, to want it so badly you won't give up on yourself or the work.

When I was a child, my mother was getting her master's degree in education, and she practiced on my sisters and me. She would have writing workshops each summer morning, and we'd sit at the oak table in our cottage at Hubbard's Point. She'd tell us to write a story about crabbing at the end of the beach, or swimming out to the raft, or to compose a paragraph about the clouds in the sky, or something beautiful or ugly or enchanting or disturbing we'd seen that week. In that way, she helped us realize the dailiness of writing, the way our ordinary lives could add up to an essay or a story.

When I was a child, my mother was getting her master's degree in education, and she practiced on my sisters and me. She would have writing workshops each summer morning, and we'd sit at the oak table in our cottage at Hubbard's Point. She'd tell us to write a story about crabbing at the end of the beach, or swimming out to the raft, or to compose a paragraph about the clouds in the sky, or something beautiful or ugly or enchanting or disturbing we'd seen that week. In that way, she helped us realize the dailiness of writing, the way our ordinary lives could add up to an essay or a story.

Years later I began holding writing workshops--one day each summer, never planned in advance, just when the spirit moved me--and I'd invite children from Hubbard's Point to come to my house for a few hours of writing. Frequently the cats would join in, sitting on my desk (including Tim and Emelina, shown here in their favorite basket), and providing inspiration.

It is important to be steady and write every day--you must actually write and not just read about writing, dream about writing, or look online for other people writing about writing. You have to do it. And you have to train yourself to be good at it.

Thursday I had the privilege of speaking to Joe Monninger's English class at Plymouth State University. I met his students, told them what it's been like for me, talked about research, heard their questions about ways of writing, possibilities of publishing. Outside, the trees were turning red and gold, maybe the foliage was at its peak, and the sky over the White Mountains of New Hampshire was brilliant blue.

Joe Monninger

We have known each other since 1980, or maybe 1981, we always seem to lose track, but we know it's a long time. I first met Joe Monninger when we were living in Providence, Rhode Island. We'd get together with our spouses for long cozy dinners at their apartment on Transit Street or ours on Fox Point, and we'd talk about books we'd read, books we were writing, fly-fishing, places we wanted to travel, sharks, dogs, our families. I'd tell Mim stories--about my grandmother who'd grown up in Providence and who'd done tons of things that made for good tales. Years later they lived in Vienna and we lived in Paris, and we visited them, and once met for Thanksgiving roughly halfway in Strasbourg, where we nearly drove off a mountain in a blizzard while visiting Haut-Koenigsbourg. Time went on, marriages ended, Mim died, Joe moved to New Hampshire, where he's an English professor at Plymouth State University, I stayed in New York, and we both kept writing. Between us, we've written a shelf of novels, including one together, The Letters.

He's a touchstone, that's for sure. We love nature and tell each other what birds we've seen that week--he has cedar waxwings in the crabapple tree, I had a red-tail hawk in the park on Tenth Avenue. A shark story doesn't occur on the planet without one of us alerting the other about it. He loves his dog Laika, I love my cats Maisie, Emelina, and Tim. We still talk about writing, and recommend books-- Carson McCullers, Cormac McCarthy, John D. MacDonald, Robert B. Parker are a few, and we both love non-fiction about nature, adventure, exploration, and he'll often slide a poem my way, and I'll do the same to him. He's one of my first readers, and I've been honored to be his. So many of his novels are favorites of mine, and I was so touched when he dedicated The World as We Know It to me.

Visiting him this week has been a great treat. What a New Hampshire idyll--a hike around Lake Tarleton, listening to owls in his back yard, watching the blood moon rise over the White Mountains, hanging out at Plymouth State, and spending time with his lovely dog Laika and kitty Foxy. I feel lucky to have such a great friend, and to have stayed close all this time.

*the photo behind Joe on his office filing cabinet is of Cheyenne--a TV character we both loved as kids, and it's autographed by Clint Walker, the actor who played him, my Christmas gift to Joe a few years back.

** Joe is also a certified New Hampshire Guide, should you ever want someone to take you hiking or show you the secret fishing spots.

Road Odyssey

Here's a fascinating essay by Vanessa Veselka: The Lack of Female Road Narratives and Why it Matters.

I thank my writing pal Joe Monninger for sharing it with me and therefore sending me on a remembrance-of-road-odysseys-past. I went through a hitchhiking phase in my teens, and I sometimes have nightmares of a couple specific close calls. One happened somewhere between Old Lyme CT and Hightstown NJ; it was early October, after a summer at the beach, and I missed one of my beach friends so much I decided to hitch down to visit him in boarding school.

In this space I normally write about the nature of summer friendships, the depth of love for my beach friends, but Vanessa's essay takes me to a different place, to the reality of what happened on the road. There I was--17, maybe?--standing thumb-out on an I-95 entrance ramp, so convinced of my own invincibility that I climbed into the cab of an 18-wheeler. I can't picture the driver, but I can see that truck--red cab littered with fast food wrappers and a dark curtain behind the seats. "Check it out back there," he said. "It's where I sleep." That was the first moment my stomach flipped.

I felt brave, resourceful. That made me reckless, but I only know that now, from the distance of many years. If I think of my nieces doing what I did, I'd lose it. Yet even after that ride in the big rig--and the driver's innuendo and invitation into the back and my opening the door and jumping out at a toll booth--I kept hitchhiking. I got to Hightstown and later made my way back home. When my younger sisters were visiting one of their boyfriends in Warren VT, I hitched north through thickly falling snow to meet them.

Right after our father died my sisters started hitching with me--great older sister, wasn't I? The the three of us were heading back to Old Lyme from Newport RI and got picked up on Route 138 by some creep in a rattletrap who told us he had beagle puppies at home and would we like to see them? We scrambled out at the next exit, climbed the ledge that bounded the ramp, and walked for miles along the crest until we got tired and called our mother to pick us up.

Nothing disastrous happened, except perhaps to our psyches. Stepping so close to the edge, courting danger, has a serious half-life. You might not be conscious of it, but the what-ifs visit your dreams. When I was young I was searching for something--I'd push myself to do things that must have scared me at some level--when I think of them now I marvel that I survived, thrived, and wrote about them in short stories and novels. I feel guilty for taking my sisters on that part of my own strange journey, but back then we were so inseparable it would have been unthinkable to leave them out.

Come to think of it, my new novel, The Lemon Orchard, is about journeys. Traveling far from what is comfortable to find something you're not even sure you need... Maybe that's just life; it's certainly been my life.

[Image: The Highwayman by Linden Frederick]

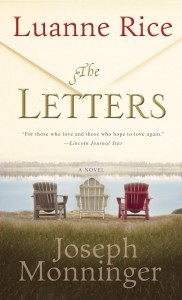

the letters! (a novel)

Time alone, a fresh piece of stationery, the right pen, the chance to think deeply and let feelings flow. Before I wrote novels, I wrote letters. To friends, family, people I love, people I wanted to know better. Letters turn me inside out. I’ve written letters that are truer than true. I’ve told secrets in letters. I’ve mailed letters filled with emotions so raw, I’ve wanted to dive into the mailbox to get them back.

The Letters, a novel written with one of my oldest and dearest friends, Joe Monninger, is out in paperback on August 28th. It’s filled with real-live letters between characters we created. Writing them startled and thrilled me. I can’t wait for you to read them.

Here is more about our friendship and writing process:

JOE AND ME

We met in 1980 at a café on Thayer Street. I’d answered his ad in the Providence Journal. He was a professional writer and for a fee would critique work. I was burning to be published. He was married to a woman in the Brown writing program. I’d been married for two months to a just-graduated lawyer. We were all so young.

His name is Joe Monninger, and sitting at Penguins, he read my stuff. I gave him a short story about three sisters whose father caroused with ladies of the town. He showed me a story about a boy fishing with his dad, getting the fishhook caught in his palm. His dad took it out, and the boy didn’t cry.

Instead of charging a fee, Joe invited my husband and me to dinner. He and his wife lived on Transit Street, the top floor of a three-family house, under the eaves. Bookcases lined the crooked stairs. Joe’s office was on the landing, dark and cozy, no window. His wife covered her typewriter with a pair of his boxer shorts. She made boneless chicken breasts, bought from the chicken man who drove around Fox Point playing “La Cucaracha” on his horn, and she pounded them flat on the kitchen floor between sheets of wax paper with an iron skillet while we watched.

We had dinner often. We drank scotch and told stories about our families and the dark side of nature. Joe and I loved shark stories, and collected them. We’d act out skits, our own form of improv. “Be a couple at the prom,” I’d say, and Joe and his would shyly dance. “Be Mim at the gift store,” they’d say, and I’d act out my grandmother being outraged at the price of a ceramic eggplant.

After dinner, they’d walk us down to the street. Passing the bookcases, they’d grab volumes, press them into our hands. Many of those books were biographies or collected letters: Carson McCullers, Virginia Woolf, Maxwell Perkins, Hemingway. I’d take the books home and get lost in writing lives.

Fast forward: time went by, and our first marriages ended. Joe and I remained friends along the way. We wrote to each other, knowing how important our connection was: we had witnessed each other’s youth. We had known each other’s first loves. We knew the sources of each other’s writing, inspiration, fishhooks.

One day we had an idea. I can’t remember whether it was his or mine. But we decided to merge two of our great loves from the early days: literary letters and acting out scenes. What if we took on personas? Became characters? We would write about people on the verge of divorce—we’d both been there. We’d incorporate nature and art. We needed names.

I became Hadley, after Hemingway’s first wife. He became Sam, because I wrote him he had to have a short, punchy name like “Joe.” Our last name is West, in honor of Tim West, a surfer from Half Moon Bay, who survived a great white attacking his board at Maverick’s one December day.

We wrote letters in character. And The Letters, our novel, took shape.

We had a son, Paul, our good, beautiful boy, who dropped out of Amherst to go teach the Inuit in an Alaska village, and who died. Our marriage couldn’t survive his death. Our desolation and grief and love and rage streamed into our letters. Hadley went to Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine, to try to quit drinking and start painting again. Sam flew to Alaska to search out the site where our boy died.

Even now, we find it hard to believe we don’t have a dead son.

Joe and I never spoke on the phone, never saw each other, not even once during the process. We never discussed or planned what would happen, how the story should unfold. The writing had its own life, the writing was all.

Life is full of mistakes and kindnesses, and what love can’t heal, fiction can.

And I love Joe. He’s my writer friend, the one who knows me best, who knows where the bodies are buried, and who tells me about sharks. We wrote The Letters. And we’ll keep writing.

my favorite blog

i came upon this blog about a year ago, and was instantly drawn in. veronique de turenne writes about malibu, nature, dogs, books, life with such heart, soul, and dry humor. she's a wonderful writer; i sent her an unabashed fan letter, and we became fast friends. we already have a tradition--having dinner on solstice nights. she introduced me to diesel, and it's become one of my favorite bookstores.check out yesterday's post, and click on the word "friend" to see why this particular post tickles me so.

but then go back, and enjoy veronique's writing and photographs. you'll feel you spent the day--or a few years, depending on how far back you read--in malibu. not the glitzy, tabloid version, but the wilderness where the santa monica mountains meet the pacific ocean...the malibu i love. incidentally, to make the circle complete, my fascination with cheyenne is shared by one of my favorite writers--joe monninger.

her an unabashed fan letter, and we became fast friends. we already have a tradition--having dinner on solstice nights. she introduced me to diesel, and it's become one of my favorite bookstores.check out yesterday's post, and click on the word "friend" to see why this particular post tickles me so.

but then go back, and enjoy veronique's writing and photographs. you'll feel you spent the day--or a few years, depending on how far back you read--in malibu. not the glitzy, tabloid version, but the wilderness where the santa monica mountains meet the pacific ocean...the malibu i love. incidentally, to make the circle complete, my fascination with cheyenne is shared by one of my favorite writers--joe monninger.

Providence

LITTLE NIGHT comes out tomorrow, the very same day the Transit of Venus will occur for the last time in our lifetimes. Coincidence? I'm not sure...

Some of you know how inspired I am by nature, especially celestial events. The full moon on the ocean enchants me. I've never missed a Perseid meteor shower--every August 11th night you'll find me on a beach blanket, watching for meteors to streak across the sky. Sometimes it's raining or too cloudy to see, but I still try. This year the planets have been lining up at dusk, sometimes with the crescent moon, to cast a spell and remind us not to remain overly earthbound.

LITTLE NIGHT comes out tomorrow, the very same day the Transit of Venus will occur for the last time in our lifetimes. Coincidence? I'm not sure...

Some of you know how inspired I am by nature, especially celestial events. The full moon on the ocean enchants me. I've never missed a Perseid meteor shower--every August 11th night you'll find me on a beach blanket, watching for meteors to streak across the sky. Sometimes it's raining or too cloudy to see, but I still try. This year the planets have been lining up at dusk, sometimes with the crescent moon, to cast a spell and remind us not to remain overly earthbound.

The title, LITTLE NIGHT, has layers of meaning...I hope you'll discover them when you read the novel. They're all connected to love, and the mysterious ways we move in and out of the dark with each other. There are secrets in the sky and in our hearts...tomorrow the Transit of Venus might help translate a little of both.

When I was a young writer I lived for a short time in Providence Rhode Island--the city of my grandmother Mim's birth. I and my then-love lived at the corner of Benefit and Transit Streets and became best friends with two writers who lived in an old Victorian house at the other end of Transit. They occupied the second floor, and there was a crooked staircase lined with books, and he wrote under one eave on the landing, and she wrote under another eave in the kitchen, and she covered her typewriter with his boxer shorts--long before computers--and we were all in love and great friends and talked about books and fly-fishing and our lives and worst fears and fascinations and acted out sketches of our families and first dates and everything else while eating cozy dinners and drinking much scotch.

There was something about that house. The fact it was on Transit Street explained some of the magic. The street was named after the Transit of Venus, a phenomenon observed in Providence in 1769 by Joseph Brown and his brother Moses using a telescope from the top of a tall wooden platform. The event was commemorated by the naming of two Providence Streets--Transit and Planet.

I wrote one of those writers today to ask about the street, and he replied: It was named after the Transit of Venus. And it happens once every 100 years. I don't know much more about it. Did you know it was scheduled for your book date?

Actually I hadn't put that together. But it seems auspicious, considering that LITTLE NIGHT is dedicated to him. We've stayed friends all these years, still bound by our loves of books, family, fishing, sharks, celestial events, dogs, cats, and a thousand million other things. We wrote THE LETTERS together. It's a paradoxically singular experience, writing a novel with another person, and I can't imagine doing that with anyone but Joe.

LITTLE NIGHT, long friendship, the Transit of Venus; it's all Providence.

yellow knife

yellow knife, carried from africa in the pocket of a ditch-digging

peace corps writer;

a gabon viper once clung

to the netting of his tent

while he lay sleepless below.

we all need shelter and books.

all these years later

i keep the knife close.

and carve initials

on the rails of the old bridge

not because i think it's mine,

but because i know it is not.

Paris

(Photograph by Peter Turnley, Café Ma Bourgogne, Place des Vosges, Paris, 1982) Lydie McBride occupied a café table in the Jardin du Palais Royale and thought how fine it was to be an American woman in Paris at the end of the twentieth century.

That is the first line of Secrets of Paris, a novel I wrote when I was, well, an American woman in Paris at the end of the twentieth century. The novel was first published by Viking in 1991 and will appear again on January 25.

(The original hardcover jacket.)

(The original hardcover jacket.)

My time in Paris was romantic, literary, adventurous, tragic, and haunting. I wrote in a garret, the maid's room on the top floor of a Belle Epoque apartment house. Every day I walked from the Pont de l'Alma to the Ile St. Louis, and back.

My walk took me past the Louvre, which I visited often.

I began to imagine setting a section of my novel in the museum's storerooms, where treasures hide, ghosts live, and a madwoman roams. I was inspired by the letters of Madame de Sévigné (February 5, 1626 – April 17, 1696) Mainly I drew on my own expatriate life--being in Paris with a man I loved, wanting to live in the city forever, yet missing home so much.

Most of Madame de Sévigné's letters were written to her daughter, and their connection touched me deeply. My mother had gotten ill while I lived on Rue Chambiges. Being so far from her, especially during that time, was very hard.

We wrote each other countless letters, and then she came to Paris to have chemotherapy at the American Hospital in Neuilly. Rock Hudson, dying of AIDS, was a patient at the same time. We passed Elizabeth Taylor in the hall. The intensity of everyone's sorrow...our family's, theirs.

Gelsey, my mother's Scottish Terrier, came to live with us. She traveled in cars, on the Metro, the TVG, Air France, and trans-Atlantic on the Queen Elizabeth II. When I would walk Gelsey in my neighborhood--she adorable, me writer-disheveled in jeans and a bomber jacket--fashionable women shopping at Dior and Givenchy would coo and pet her while I gladly remained invisible.

I met a Filipino woman, "Kelly," working as a maid in the Eighth Arrondissement, whose great dream was to reunite with her sister living in the United States, and open a fish market together. She had been smuggled into France from Germany by a Filipino driver of exiled Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. The driver had many duties, including a weekly visit to the design house of Nina Ricci on Avenue Montaigne, to purchase hundreds of hand-embroidered white linen handkerchiefs which the Marcoses would use instead of tissues, at a time when millions in the Philippines suffered in poverty.

These are a few of the stories that lived with me in Paris. The city's beauty hides secrets.

While living there my novel Angels All Over Town came out in the States. One day i received a call from a man saying he was a Newsweek photographer and had been assigned to take my picture for the magazine--an article about first novelists. I thought it was my friend Joe Monniger, a fellow writer living in Vienna, playing a joke on me (he would,) but the photographer gave me a number and told me to call back, and the operator answered, "Newsweek" and put me through.

Thus I met Peter Turnley, amazing, talented, award-winning, war correspondent, artist, photographer. We spent the day touring Paris, Peter photographing me on the Champs-Élysées, at Invalides, on the Pont d'Alexandre III, on the Champs de Mars beneath the Eiffel Tower, on the banks of the Seine.

We had coffee at storied and literary Fouquet's and he told me of covering world conflicts, dodging fire, seeing war upfront. I wondered how he'd gotten stuck taking pictures of a first novelist. His last shot of the day--using up film--was black and white, on my balcony. I'm squinting into the day's last light, thinking about Paris and war and Peter dodging bullets. That's the picture (shown here) the photo editor chose.

The photo shoot made it into my novel Crazy in Love. In the movie, the photographer is played by Julian Sands.

Over the years I have viewed Peter's work with admiration. His Wikipedia entry begins: Peter Turnley is a photojournalist known for documenting the human condition and current events. Over the past two decades, he has traveled to eighty-five countries and covered nearly every major news event of international significance. His photographs have been featured on the cover of Newsweek more than forty times. A renowned street photographer who's lived in and photographed Paris since 1978, Turnley is one of the preeminent photographers of the daily life in Paris of his generation.

That is Peter, exactly. How lucky I was to be photographed by him, and to become his friend. His images capture for me the essence of Paris then and now.

On Facebook my team often holds giveaways. This one will stand out from all others. We'll be offering signed copies of Secrets of Paris, but also a print, for one single reader, of one of my favorite of Peter's photographs (Peter Turnley, Paris, 1991):

The black and white photograph is traditional collector museum quality archival prints on fiber paper. Each print is signed on the front and back by Peter Turnley, and signed on the back by Voja Mitrovic, world renowned master printer who has been a long time printer for Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka, Rene Burri, Peter Turnley, and many others.

If you wish to be eligible to win a copy of the novel as well as the photograph, please just click this link to Facebook and "like" the page. Among other things, we have a wonderful, supportive group.

I'll sign off with this quote. It's from a letter by Madame de Sévigné and appears on page one of Secrets of Paris:

What I am about to communicate to you is the most astonishing thing, the most surprising, most triumphant, most baffling, most unheard of, most singular, most unbelievable, most unforeseen, biggest, tiniest, rarest, commonest, the most talked about, the most secret up to this day, the most enviable, a fact a thing of which only one example can be found in past ages, and moreover, that example is a false one; a thing nobody can believe in Paris (how could anyone believe it in Lyons?). ~From Madame de Sévigné, December 1672

Life of a Book

The Silver Boat feels very alive to me. It's only October, and the novel won't come out until April 2011, but already it's making its way in the world. I'm always amazed at the secret, labyrinthine, enchanted life of a novel, and I thought maybe you would be, too. First it has to be written. That in itself is pure magic and spirit. The initial idea lodges in my heart, I live with it for some time, and soon I find yourself looking for a pen, jotting down the first lines, the character's name, a vision of where she lives, what she sees. Or maybe the idea is big and fully formed enough for me to go straight to the computer, open a new file, and let the story flow.

Living with the novel, listening to the characters, is more privilege and joy than work. To wake up every morning, hit the desk and start up where I'd left off the night before, let my characters lead me deeper, is the best. I'm never happier than when writing.

When I've written the last page, reread the draft, feel it's time to let it go, I send the manuscript to my agent and my publisher. For many years, since my first novel, I've incorporated talismanic elements into the submission; I almost always find a card, or a postcard, that somehow illustrates the essence of my new novel. I still remember the one I used for Crazy in Love: Winslow Homer's Summer Night, a painting of a couple dancing in moonlight on the beach.

The postcard I included with the manuscript Secrets of Paris, was a photograph of a woman writing at a Paris cafe, and actually inspired Viking to use it as the book cover.

Talismanic postcard or not, There are some tense days, waiting for a reaction. When it comes, if it's good, I'm thrilled and ready to dig into the next phase--revision. The first draft is a gift, and revision is really work.

Finally the novel is finished, accepted, and a new round of fun begins. Cover sketches, proofs, choices. Pam, my editor, had a very clear idea for The Silver Boat's cover; I remember sitting in her office when she showed it to me. I loved its simple beauty, luminosity, and the way it drew me in to the novel.

Now the ARCs (advance reading copies) are finished, being sent into the world. Publishing industry people will read it. Peggy, the agent in charge of foreign rights, went to the Frankfurt Book Fair, and showed the cover to foreign publishers, and reported back that they loved it.

Tonight I'll have dinner with a woman from LA who will help publicize the novel. I love all these moments, pre-publication, because I see how each one helps the book come to life. Books are like the Velveteen Rabbit--they have to be read and loved for them to truly be alive.

I have a shelf of much-read and greatly-loved books--my own private Velveteen Rabbits. Actually, The Velveteen Rabbit is one. Honor Moore's The White Blackbird, Alice Hoffman's The Story Sisters, J.D. Salinger's Franny and Zooey, Laurie Colwin's Happy All the Time, Ann Hood's The Red Thread, Joe Monninger's Eternal on the Water, Katherine Mosby's Twilight (published way before the other Twilight,) Rumor Godden's Little Plum, Marguerite Henry's Misty of Chincoteague, James Joyce's Dubliners, Sylvia Plath's Letters Home, Gretel Ehrlich's The Solace of Open Spaces, Pam Houston's Cowboys are my Weakness, Braided Creek by Jim Harrison and Ted Kooser, and so many more: I've read and read them, loved them all, in some cases until they're threadbare.

April seems a long ways away, but I know it will come fast. Actual publication is something else again--exciting, satisfying, and I never tire of walking into a bookstore and seeing my novel on the shelf. But by then I'm usually deeply into a new novel, with a group of new characters, and a whole new life is underway. Another book, another life.