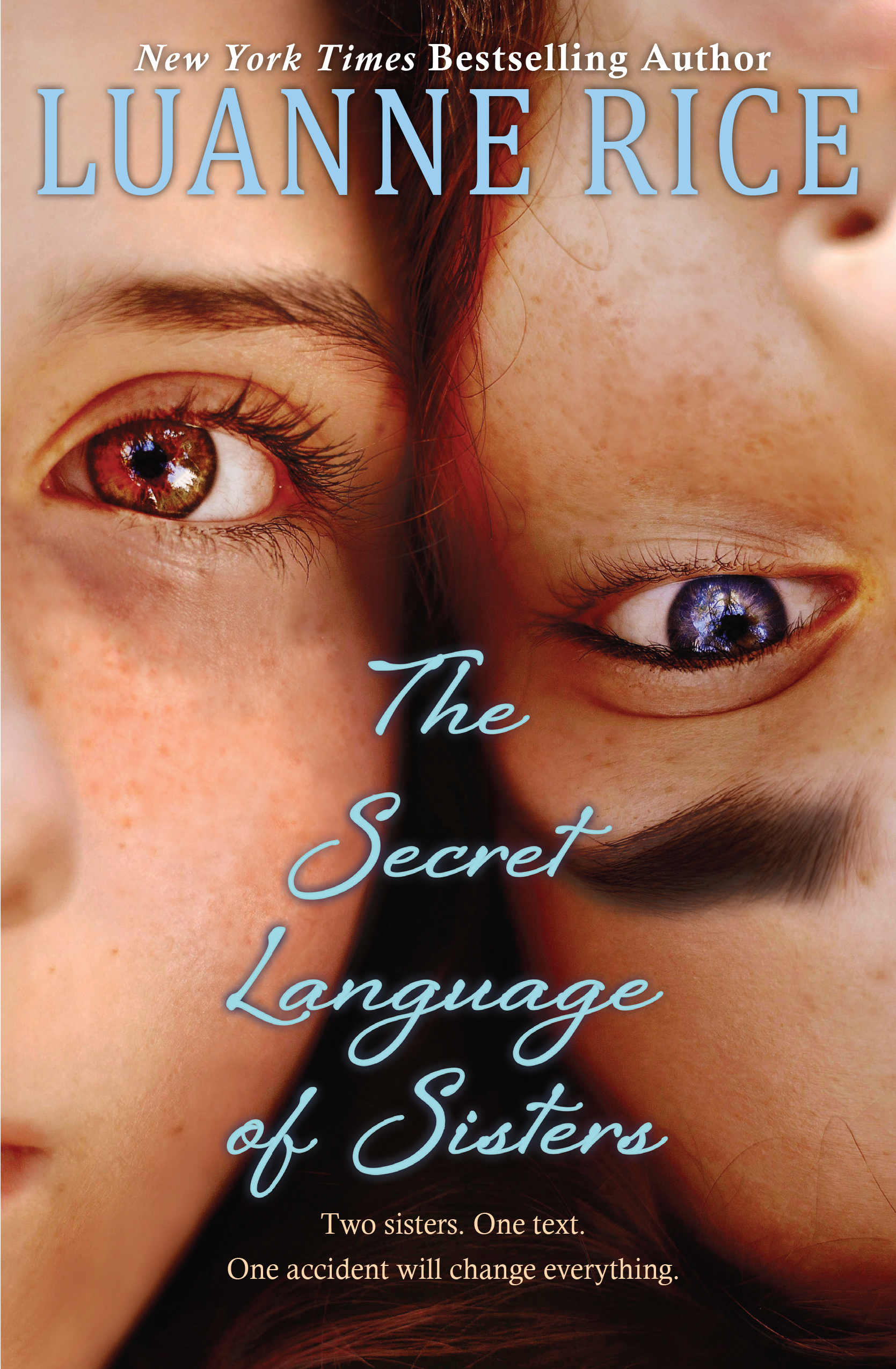

Just in time for the publication of THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF SISTERS (Tuesday! February 23!) I have a brand new website. I thank Adrian Kinloch, my long-time web person, for creating this one, and the last one, and the one before that.

Read MoreWinter Institute

Winter Institute is amazing and what a joy it was to spend time with independent booksellers. I was invited by my wonderful publisher, Scholastic (book fairs! book clubs! Harry Potter! The Hunger Games!) to join the party in Denver CO and talk about my first YA novel, The Secret Language of Sisters. My fellow authors were Sharon Robinson (great writer, daughter of Jackie, my mother's idol) and Derek Anderson (amazing artist and writer of picture books) and we celebrated the fact that writing for children (in my case teenagers) is a very special calling. Their warmth and welcome into this new world for me made me feel so lucky. On top of that, we were taken care of, introduced, and nurtured by Scholastic's inimitable Bess Braswell and Jennifer Abbots.

Read MoreThe Secret Language of Sisters

I'm thrilled to let you know The Secret Language of Sisters is now out in paperback. So many readers discovered my first young adult novel in hardcover, and I have loved hearing from you on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. You've really welcomed me to the world of YA! Thank you for that! Love, Luanne xxoo

IndieBound • Amazon • Barnes & Noble • iBooks • Google Kobo • Books-A-Million • GoodReads • Scholastic (Publisher)

Read MoreOnce in a Blue Moon

A blue moon is a celestial rarity and occurs when there are two full moons in one calendar month--such as the one today. It refers not to the color of the moon, but to the wonder. The title of my fifth novel (first published in 1993) is a play on that, and refers to the rare, once-in-a-lifetime love between Sheila and Eddie, the matriarch and patriarch of the Keating family. The title also refers to a long-disappeared section of sailor's bars and nefarious doings in Newport, Rhode Island. The name "Sheila" was inspired by Sheila Dingley Mularski, one of my favorite little girls, who has grown up to be a Title One reading teacher, working with 10-12 year olds. Her school has a small library, but no librarian, so Sheila started volunteering her lunch hour to help kids check out books. Could we take a moment of appreciation for Sheila as well as your own favorite teachers and librarians, people who encourage and celebrate reading?

I have very happy memories about the publication of Blue Moon... The Happy Carrot had just opened in Old Lyme, Connecticut. It was a wonderful independent bookstore owned by Paulette Zander, and this was the first reading she'd hosted. She decorated the store windows in such a mystical way, full of blue moon-inspired art, and it was the first of many great book events we would have together.

My launch party was held at the Old Lyme Inn--then owned by my dear friend Diana Atwood Johnson, who ran it like an artists' retreat and literary salon (she's an artist herself, I was honored to introduce her at last summer's exhibition of her bird photographs at the Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts.) For the Blue Moon party she served blue cocktails and seafood delicacies. In the novel, Shore Dinners were served at the Keating family restaurant, and Diana outdid herself recreating the lobster-and-clam-bakes cooked by the Keatings. She decorated the inn so beautifully, and we invited old and new friends. I remember being totally surprised and delighted to look up and see the Reducers, a band I love, walk into this classic New England inn in all their black leather punk glory.

Blue Moon was later made into a CBS Movie-of-the-Week. It starred Sharon Lawrence, Jeffrey Nordling, Kim Hunter, Richard Kiley, and Hallie Kate Eisenberg, and was filmed in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, one of the most beautiful seaside towns I've ever seen. My love for Nova Scotia had already begun, but it certainly deepened during my visit to the set.

Happy memories...I am glad for the chance to share them with you. The sky does inspire me. I hope you look up tonight and all nights and enjoy what you see...

No Animal is an Island

I was lucky enough to read Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel by Carl Safina in galleys, a few months before publication. Carl and I had been introduced via email by a mutual friend, Pete DeSimone of Starr Ranch Sanctuary, and we had corresponded about owls and whales. A snowy owl had been visiting Carl's beach on eastern Long Island, and knowing my interest in owls in general, snowies in particular, he sent me photos and reports about the visitor. His book The View From Lazy Point had long been a favorite of mine. He makes science personal, writing about the beach he loves, the species he's studied, the world travels he's taken to observe animals in varied habitat. I like that he doesn't hide his love for the oceans and his commitment to the environment.

His new book Beyond Words, is brilliant, gets truly and deeply into the mind and emotions of animals--the inner lives of elephants, wolves, and killer whales. He talks about families, love, loyalty, betrayals, intense grief of different animal populations. He discusses endangered species, in some cases the erosion of protections, the reality of humans hunting for sport and trophies and monetary gain. The sections on elephants, what happens when humans poach them for ivory, delineate with such compassion the devastation and grief felt by the family members left behind.

His work with killer whales--a name he prefers to orca, deriving as it does from the Latin Orcinus Orca and referring in an inescapably demonizing way to Orcus, god of the underworld--took him to San Juan Island and Haro Strait. He discusses two populations--transients, who hunt mammals, such as sea lions--and residents, who eat fish, mainly salmon. With Ken Bascomb he listens to the whales via hydrophones, chirps and whistles and clicks. He differentiates their echo-sounding sonar from communications. They form strong family units and stay together for decades, for life. They kill for food, and it's brutal to watch the transients go after seals or California Gray Whales. But killer whales are social beings, very curious, and love to play; they seek attention from other killer whales and from people they encounter. Carl quotes an observer who said they "look through their otherness at you."

He writes about the tragedy of killer whales being netted, taken captive for aquarium exhibits--what it's like for a mother whale to see her baby captured, unable to stop what's happening. And how the baby whale feels, ripped from a mother and the voices of her family, "going from the limitless ocean to the confinement of a concrete teacup, the terror and confusion..."

Overfishing and chemical run-off contribute to a combination salmon shortage and toxic load that is endangering killer whales. They can live forty to fifty years, but the population isn't reproducing. Recovery of the salmon fishery doesn't look likely, and the Pacific Northwest's logging industry isn't about to stop using river-killing fertilizer and flame retardants that get into the food chain, into the plankton eaten by the fish eaten by the seals eaten by the whales.

After reading Beyond Words I felt so happy to give it a quote. Carl came into New York to record the book for audio, and we finally met. He's a kindred spirit. Now that we're friends, do you think I can ask him to write something on cats?

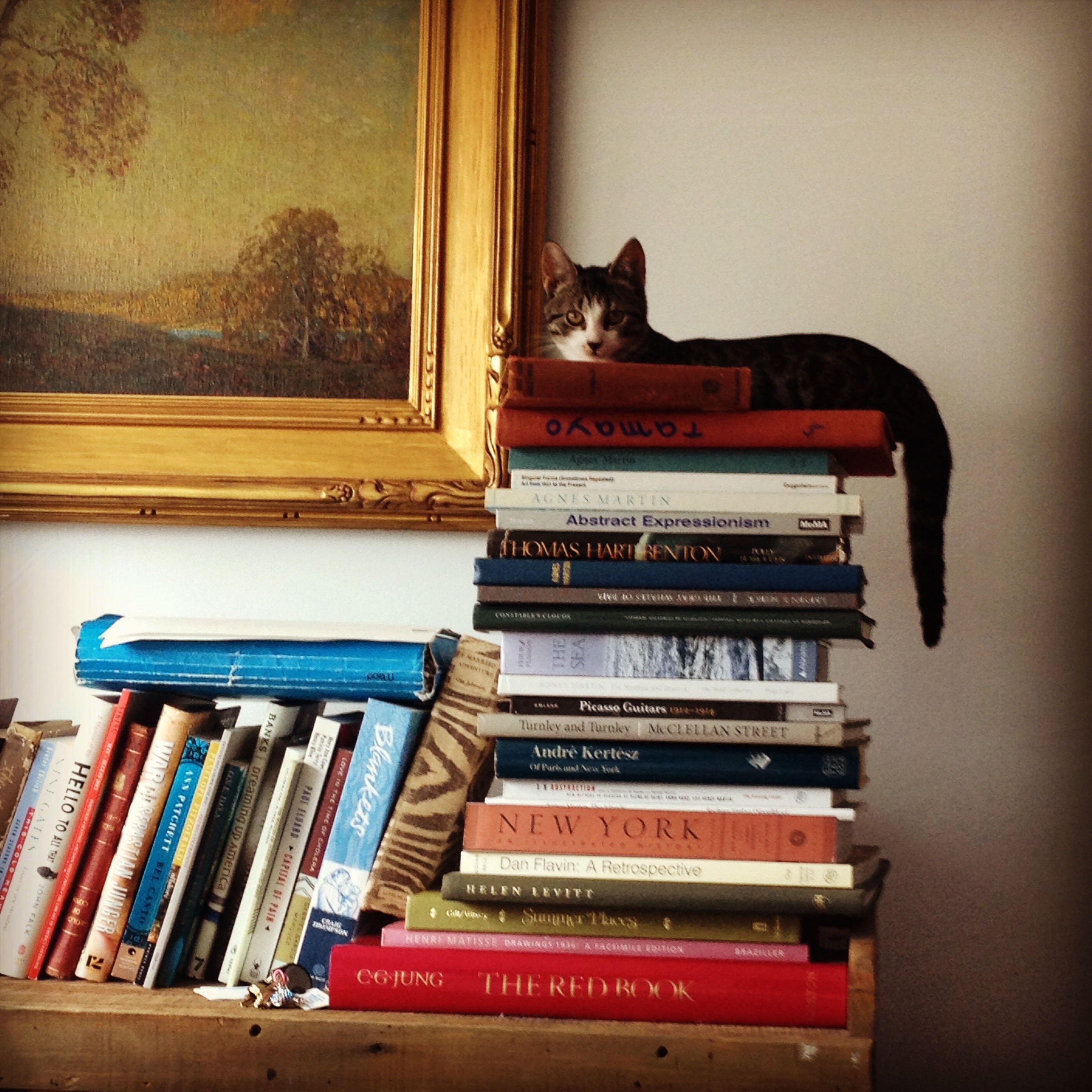

I want to know what mine think and feel. I keep them inside partly for their own protection and also to keep them from following their natural instincts to hunt birds and mice, but they are still wild things, with distinct personalities, and eyes full of soul. When Maggie died a few years ago, I watched Mae-Mae and Maisie grieve. The two survivors returned again and again to the spot where they'd last seen Maggie, before I buried her. They meowed, and it sounded like keening. I would have given anything to be able to read their minds, to understand their feelings.

Carl's book helps me to know that such understanding is possible. Translation may be harder, but I keep trying. I share my house with these creatures, and we all share the planet with a whole lot more, and I am grateful for all of them, and for this book.

Species are connected to each other, and we to them. When we forget that, we forget our humanity.

As I write this, social media is full of new about the death of Cecil, a thirteen-year-old lion in Zimbabwe. Walter J. Palmer, an American dentist, paid $55,000 to hunt him down. Cecil was lured out of Hwange National Park, the sanctuary where he lived, and was shot with a bow and arrow. There's a photo of Palmer grinning over the corpse. Cecil looks majestic and dignified even in death, but they beheaded him and left his corpse to rot. The dentist's grin makes me sad--the whole story does. I wish I could have given him a copy of Carl's book. Maybe Cecil would still be alive if he'd read it.

Maybe the planet will be healthier if we all do.

No Man is an Island

by John Donne

No man is an island, Entire of itself, Every man is a piece of the continent, A part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less. As well as if a promontory were. As well as if a manor of thy friend's Or of thine own were: Any man's death diminishes me, Because I am involved in mankind, And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.

Agnes Martin: a Gentle Obsession

The idea of a pilgrimage is powerful, and carries spiritual overtones, and I made one recently, with a good friend, to see work by Agnes Martin at the Tate Modern in London. That our destination was not a religious shrine but a gallery filled with paintings made the journey no less transfiguring. Agnes was born in Canada but is known as an American artist; the exhibit is at the Tate Modern in London, and it seemed particularly important to me that the pilgrims in this case--two American women, my friend and I--travel to see her in a country not our own. The paintings in the Tate exhibition are soaring, serene, floating, yet charged with energy. The canvases are large, some of them familiar to me for having seen them in other galleries, and I felt myself dissolve moving through the rooms. Agnes Martin sought perfection, and for all the apparent similarity in her canvases--in size, color, lines, in the rectilinear grid that had begun to appear in her work by 1958, in the parallel stripes that by the mid-1970's had mostly replaced the grid--it is their imperfections, the small variations, the thickened pencil lines--that pulled me into her life, gave me the sense of her doing this over and over, starting again, striving for an ideal, that filled me with emotion.

Every painting touched me in a different way, but I had to return, after going through the exhibition once, to the center room where The Islands I-XII are installed. Twelve canvases, painted in shades of white, are displayed together, as Agnes intended them to be. The paintings are luminous. They are acrylic and graphic pencil on linen, and although from a distance they seem to be all-white, up close the delicate variations reveal themselves in thin white bands and thicker ones, pencil lines and brushstrokes.

Agnes is both local and boundary-less to me. She lived in New York City, as I do, and when I see the photo of her sitting on the rooftop at Coenties Slip, I imagine her needing and space and air--her painting are elemental--I think of her studio, a former sailmaker's loft in a small brick building by the South Street Seaport that still stands in the shadows of the financial district's towers--and wonder if the walls of both this city and the studio, despite the salt air and views of the East River, were closing in on her.

She left, just as her reputation was soaring, and drove a pickup across the United States for over a year before finding her place in New Mexico. She sought, or was given, visions of beauty, happiness, purity, and joy. Before leaving New York she had hospitalizations at Bellevue, a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. Those grids, meticulous works scored with intersecting lines, carefully drawn with pencil and ruler, convey to me wide open spaces. She said, "Finally, I got the grid, and it was what I wanted. Completely abstract. Absolutely no hint of any cause in this world."

Once, after viewing some of her work at Dia: Beacon, I dreamed of her grid paintings as Saskatchewan: flat and rural, the province of her childhood, fields and farms scored by roads, fences, and rows of crops. In the Tate's short film Agnes Martin Road Trip, Agnes said, "You are what goes through your mind, whether you are aware of it or not. You know. But if you can become aware of it, and and if you then can try to express it, you are an artist."

She has spoken of her mother, of her dark silences, of unhappiness. Childhood pain is the thorn in the paw of so many artists and writers, and we spend our lives trying to get it out. And maybe make things turn out differently, at least on the canvas or on the pages of a novel. Maybe she was purely abstract--the ultimate minimalist--but her titles are poignant, and when you think of what you've read about her childhood, heartbreaking--Happiness, Contentment, Happy Holiday, Innocent Love, Drift of Summer, Happy Valley.

In the sixties, diagnoses of schizophrenia were handed out freely, a catchall for all kinds of psychiatric distress. Creative people found themselves labeled and locked up. In Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances her friend and Pace Gallery owner Arne Glimcher writes of her voices. And supposedly an episode of her wandering Park Avenue in a fugue state landed her in Bellevue; but what young creative person living in New York hasn't found herself wandering some part of the city in a fugue state? I ask this in all sincerity.

I was first introduced to Agnes's work by a psychotherapist. A print of Night Sea hung in Susan's waiting room. Sitting there I would stare at it and get lost in the color blue, and the grid, and the fact it was Susan's. For me it was not Bellevue but McLean, not schizophrenia but depression, and--eventually--not New Mexico but California. Somehow Agnes and Susan and living in New York and leaving New York and emotion and the abstraction of search and perfection merged together in my own private dream world, and an obsession took hold.

Obsession and pilgrimage are strong words and I'm not sure Agnes would like them applied in relation to her. But they are real to me, and I've taken trips to "visit" her, both lengthy and just around the corner, before this one. Walks through the city, uptown to the Pace Gallery for a 2004 exhibition, frequent wanderings around Coenties Slip and the Seaport, to New Mexico to view the light-scalded landscape that inspired her later years, to Saskatchewan to see grids written on the earth, up the Hudson River to Dia: Beacon; and I've mostly returned from my California sojourn to live within sight of Dia: Chelsea.

I wanted to buy Agnes's Galisteo studio. It was for sale again, a few years after her death in 2004. The desire took me over for a long time, and I am afraid I nearly drove a New Mexico realtor crazy. The revelation came slowly, as many dream-killing realizations do, that the remodeling job done after her death, the fancy kitchen and other updates, would have wiped out the feeling of her living there, that I wasn't likely to find her ghost or any traces of her life left behind. They would have been curated away.

I go to Coenties Slip on Sundays when Wall Street is empty. A new management company has just taken over the building where Agnes had her studio. Maybe I should be glad it still exists at all; it is part of the landmarked block where Fraunces Tavern stands (George Washington bade farewell to his officers there) and won't be torn down, but the old sailmakers' lofts are getting a re-do. The marketing website touts proximity to the South See Port (you read that right) and all major subway lines, and to granite tubs and rain showers. The rents are high. This is the way of New York. Where do young, or any, artists and writers go now?

Agnes speaks about inspiration, of how thoughts and ideas can get in the way. Paradoxically, even as a writer of fiction, I find that true. My intuition always knows what to write, and one of the biggest challenges is getting out of its way. Out of my own way. Ideas take a back seat to character. If I start thinking I know what the character should do, instead of letting her determine her own course, I'm in trouble. The character needs space. Meditation helps. Emptying the mind of worry and the impulse to control helps. And seeing art, getting lost in it, helps. The character rules.

"I paint with my back to the world," Agnes said. And she did, leaving New York City to live as a recluse in New Mexico. But when you view her work, you've been invited onto the mesa, and it's luminous.

The exhibition will travel to the United States later this year. But I needed to see it in London.

YA Cover

I’m so excited to reveal my cover for my YA debut, THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF SISTERS (Scholastic, February 23 ’16) I love these two sisters and feel the cover captures their amazing connection (as well as their separate secret inner worlds,) and I can't help turning it upside down to look into each of their eyes.

Here is the announcement from Publisher's Weekly:

I’m so excited to reveal my cover for my YA debut, THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF SISTERS (Scholastic, February 23 ’16) I love these two sisters and feel the cover captures their amazing connection (as well as their separate secret inner worlds,) and I can't help turning it upside down to look into each of their eyes.

Here is the announcement from Publisher's Weekly:

Bestselling adult author Luanne Rice sold her YA debut, The Secret Language of Sisters, to Aimee Friedman at Scholastic. Andrea Cirillo at the Jane Rotrosen Agency brokered the world rights deal for Rice, noting that the book, scheduled for 2016, was pitched as The Diving Bell and the Butterfly meets If I Stay. In the novel a girl enters a coma-like state known as locked-in syndrome (a condition in which the victim is conscious but cannot move or speak) after getting into a car accident. The accident was ostensibly caused by the fact that she was texting with her sister while driving. The “locked-in” state allows the victim, Cirillo explained, to be aware of her surroundings as well as “the story of her sister, who blames herself for the accident.”

Cilantro, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme

Living in the world of whatever I am writing is my favorite place to be, but sometimes it's helpful to step outside--literally. The terrace is tiny, and high over a Chelsea crosstown street, but it is just outside my office door, and there is room for an herb garden. I grow cilantro, sage, rosemary, and thyme, and this year I have tomato plants. We'll see what they do.

Living in the world of whatever I am writing is my favorite place to be, but sometimes it's helpful to step outside--literally. The terrace is tiny, and high over a Chelsea crosstown street, but it is just outside my office door, and there is room for an herb garden. I grow cilantro, sage, rosemary, and thyme, and this year I have tomato plants. We'll see what they do. Looking east at sunset, Manhattan is painted brick red.

Looking east at sunset, Manhattan is painted brick red.  Looking west at the Hudson River and Hoboken I feel so lucky to have a glimpse of water. The boats go by, and my dreams seem to follow them. The weather changes can be subtle or dramatic, but they transform the landscape constantly. Every minute the view could be of a different city. This is true wherever we are. Clouds, clear sky, shadows, darkness change the outward details, take our imaginations in different directions. I take photos of the same scene, over and over, because I'm in awe the play of light, the drift of shadows, the way it never stays the same. Claude Monet, I get the haystacks.

Looking west at the Hudson River and Hoboken I feel so lucky to have a glimpse of water. The boats go by, and my dreams seem to follow them. The weather changes can be subtle or dramatic, but they transform the landscape constantly. Every minute the view could be of a different city. This is true wherever we are. Clouds, clear sky, shadows, darkness change the outward details, take our imaginations in different directions. I take photos of the same scene, over and over, because I'm in awe the play of light, the drift of shadows, the way it never stays the same. Claude Monet, I get the haystacks.

Last week a family knows as the Chelsea Ravens fledged. They were nesting on a building just east of here, up on the roof amid gargoyles and water towers.

They play in the sky, and I watch them dive-bomb each other. I'm not the only one who watches. And the ravens aren't the only ones who play.

They play in the sky, and I watch them dive-bomb each other. I'm not the only one who watches. And the ravens aren't the only ones who play.

Northern Light

It was winter, but I went north. I wanted the deep and dark, and I dreamed of seeing the aurora borealis. Living in New York City, I follow an aurora forecast on Twitter, and a blog about a Baffin Island expedition. One Christmas I came close to booking flights to Iqualuit--it would have taken twenty-four hours to get there--because I longed for the polar dark. I've held on to that desire for some time. My friend Bill Pullman was playing Othello at Den Nationale Scene in Bergen, Norway. So although I had been a serious hermit for a few weeks, writing and not leaving the apartment, on February 16th I flew over to see the play. Bill is brilliant in it, uncovering dangerous truths about jealousy and solitude, and the way a specific kind of aloneness can make a person go mad. Othello's undoing and explosion are exquisitely drawn. The play is directed by Stein Winge. It is one of Bill's great performances.

I explored Bergen, the waterfront, and the National Theater itself. Ole Friele, Information Manager, arranged a backstage tour. Henrik Ibsen had once been writer-in-residence, and the theater is full of history and magic, with a gilded lobby ceiling and carved boxes.

Later Gunnar Staalesen, a lifelong resident and author of mysteries set in Bergen, gave us--Kathryn and Sam, two other friends of Bill's, had also flown in from New York--a tour of town. We walked the Bryggen quay lined with colorful wooden buildings, past the 12th century St. Mary's Church, out to the 13th century stone Bergenhus fortress near the harbor's entrance. There is nothing like being shown Bergen by one of the fathers of Nordic Noir.

A steady rain began to fall. Gunnar spoke about how the town had survived layers of war and fire, and how during World War II it had been occupied by Germans and bombed by Allied aircraft. Visiting Europe always makes me look up at the sky, where my father flew a B-24 on thirty bombing missions--Bergen was not one of them. I think about him, and how he was only twenty-three years old, and about the people on the ground, and all the ones who died. There is a kind of sorrow to these visits, solemn and graceful.

I had planned on flying straight back to New York, but during the walk to the fortress I saw a Hurtigruten ferry in the harbor, and everything changed. The ships ply the fjords in a northerly route along Norway's west coast, from Bergen to Kirkenes, transporting cars, cargo, and passengers. This might be my chance to go far-north. I called on the off-chance and snagged the last cabin on the next ferry.

It was literally the last cabin--a small single all the way aft on the starboard side of Deck 6 of the MS Finnmarken--and it would be mine as far as Tromsø. We steamed out of Bergen that night, up Norway's jagged west coast in mostly calm seas. I was stunned and transfixed by the light: the silhouette of fjord walls in daylight, stark against the sky, and at night, blocking out great black patches among blazing stars.

At night we passed tiny towns nestled in natural harbors and single houses perched on cliffs, lamps glowing warmly in the wilderness. I watched until they were out of sight, and I wondered about the people inside. Were they happy? Were they lonely, or did their inner lives and the fact of being surrounded by spectacular natural beauty provide enough solace? Did every lighted window represent someone on the Internet? Is there a place on earth to find contentment, or do people everywhere imagine peace, love, and understanding to be greater anywhere but at home? I wanted to believe in their coziness.

Late one night we pulled into Kristiansund. A woman's voice came over the loudspeaker, animated and proud, telling about the heritage of the port, how it was known for dried and salted cod, that no place in Norway had produced more. She said the ship would be docked for about thirty minutes, and if we wanted we could walk to the square to see the sculpture of the "fish girl." It was midnight, and I was in my bunk. But the emotion in the speaker's voice made me get up, and I left the ship. The statue was a few wharves away. The bronze woman stands tall and proud, holding a slab of dried cod.

I found it so moving. The fishing industry is full of danger and hardship, economic uncertainty, and deep family connections to a way of life that depends on nature. Traditionally the fish haul was prepared and spread on the rock cliffs, to be dried by wind coming off the sea, and women and children tended the klippfish drying process. The fish girl worked hard, I had no doubt.

We crossed the Arctic Circle at latitude N66.33 one night. The captain told us what time to look off the starboard side. I climbed out of my bunk and saw as we passed the Arctic Circle Monument, an illuminated tilting silver globe standing on a promontory. I felt I had arrived at something, a place I had needed to be for a long time.

The feeling continued. I was in the Arctic. This was a strange emotional homecoming to a place I'd never been. I watched the landscape grow even more austere and dramatic. I scanned for whales, but was told it was the wrong time of year, they had migrated to other feeding grounds. Around Trollfjord we passed a Snowy Owl resting on a ledge, and I saw many raptors including White-tailed Eagles, also known as Sea Eagles, circling bays and mountaintops.

My reading has long taken me north. Salamina by Rockwell Kent; fiction and essays by Joe Monninger; Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez; This Cold Heaven and The Future of Ice by Gretel Ehrlich; The View From Lazy Point by Carl Safina (especially the arctic sections); and Great Heart: the History of a Labrador Adventure by James West Davidson, are some favorites, but there are many more. To actually be so far north during February, observing the landscape I had only dreamed about, eased my heart.

The planet seems less fragile there. That's an illusion, of course. The ice caps are melting, species are endangered, overfishing is a reality, and birds are losing habitat all along their migratory paths. But to see so much empty space, open ocean and uninhabited land, gave me hope that there are still some places that humans haven't totally ruined by imposing themselves everywhere and maybe won't. Then we passed an oil rig.

Being on the ferry reminds me of hibernation, a waking dream. Everything is so beautiful and extreme out there, beyond the ship's rails. Most days were cloudy, but even on the bright days the February light was muted somehow, it didn't assault the eyes and spirit, it didn't demand that a person's mood match it. The Arctic felt safe and comforting to me, as I somehow knew it would.

That is not to say that depression drives a love of the north. But depression is an edge, and so is the Arctic, of an internal landscape and of a continent. The north is remote and rugged, and the difficulties of living there are epic. Light during the winter months is clear and rare. A person who is depressed has a similar complicated relationship with light: you know you should seek it, and you sometimes feel grateful to it when you do. But the instinct is to hide from it, to find comfort and stillness by going inward.

One night, my last on the ship, I saw the aurora borealis. It might have been my first time, although I am not 100% sure. Once in about 1989, in the Old Black Point section of Niantic, Connecticut, I saw what I swore was an aurora. My sister Maureen remembers me calling to tell her to look northwest. We saw something bright and unusual and lasting in the sky, but to this day I'm not sure. And it looked very different from what I saw from the deck of the Finnmarken.

We had had just left the town of Stamsund heading north through the fjord when the captain announced there was an aurora dead ahead. He turned off the deck lights, and the night was very dark, cold, and crystal clear as we gathered at the rail. There was no moon.

The aurora began as a white band, an elongated half-oval similar to mist, ghostly but with a distinct curve just above the horizon. Within moments it had spread high and wide, above the low mountains off the port side, colors ranging from pale to bright green in organ pipe-like spikes, in parts swirling blue and pink. Over a period of thirty minutes it morphed into different patterns while maintaining the ghost of the original oval. The Big Dipper was just overhead, the handle arcing towards the port horizon, with Arcturus deep in the shimmering lights.

Throughout the night we passed through narrow straits lined with towering mountains, and the aurora came and went. At times it seemed to surround the ship. The stars were so bright behind green fire. Orion walked through it, balanced on the horizon. I stayed on deck for a long time. My hands were cold and numb, but I kept watching.

The next day we docked in Tromsø. I nearly asked if there had been any cancellations, if I could stay in my cabin and just keep going north. This might sound strange, but after the experience of the night before, seeing the northern lights, I didn't want to keep chasing them. I felt I had gotten more than I'd dreamed of--to see them above the cliffs of the fjords on a totally moonless night, with all the constellations in the background. Even now I can't explain how meaningful the light, and the dark (especially the dark--so blue and beautiful) was to me. The north in winter is a nocturne, a luminist painting.

After I got off the ship, I flew to Oslo. I had seen my friend play Othello, and I'd finally made it to the Arctic, and I'd seen the northern lights. I had every intention of returning straight to New York, but there in the Oslo airport I realized I wasn't quite ready to go home. So I hopped a flight to Paris instead.

Photos of Norway, all taken on my iPhone:

Paris, Again

Paris is home. If you are lucky enough to live to a certain age, and you've moved around some, perhaps you've had an address in a few cities, inhabited a number of dwellings. But only a few can be called home: the house you were born into, the place that shows up in your dreams, wherever you and your family currently live, and, if you have ever resided there, Paris.

I lived there for two years, exactly half my lifetime ago. I was in love. He worked long hours, so I spent a lot--most of--my time alone. My tutor was an older, very proper Parisian woman who lived in the 15th Arrondissement and who taught me many lessons along with verbs and dialogues, including the fact that Celine is preferable to Chanel.

Each day I would concentrate on learning the dialogues by walking west along the Seine, crossing the Pont Marie and Ile Saint Louis, then heading east on the Quai de la Tournelle, angling up any given street toward Odeon or Saint-Germain-des-Pres, and eventually winding my way back home across the Pont de l'Alma.

After a recent and circuitous trip to see Bill Pullman play Othello in Bergen, Norway, I wound up back in Paris. I've been there many times since moving away, but this visit felt urgent, intense, as if Paris had something my spirit could not do without. The weather was February damp and cold, encouraging hours spent reading by the window. The city has a special melancholy from November through February. I was glad not to have missed it.

Paris feels ancient, and it is. Roman baths from the 3rd century exist at the Thermes de Cluny, and more recent layers of history are visible on every step of my walk. One friend's apartment was built in the 15th century, close to the river in the 5th Arrondissement, and at night the lights of the tour boats would come through the windows and dance on the ceiling. My building was Belle Époque, ornate with carvings and balconies. The windows in most buildings are tallest on the rez-de-chaussée andpremier étage, growing progressively smaller as the floors go up because before elevators the wealthiest lived closest to the ground and the servants lived up above. I wrote in the maid's room on the top floor, and the window, although tiny, overlooked rooftops and chimneys, with a distant view of the Tour Eiffel.

On this most recent visit, I took my regular walk every afternoon. The sky stayed dark most days, but occasionally the clouds would part enough so the Seine and the building that border it turned the color of tarnished silver. Paris always fills me with nostalgia. The city doesn't change the way New York does, so it's easy to call up memories of past times: sitting for hours with Karine at Brasserie Lipp, having dinner with friends at tiny Restaurant Paul in Place Dauphine, meeting Peter Turnley at Brasserie de l’Isle Saint-Louis. (When Angels All Over Town, my first novel, came out, Peter took my photo for Newsweek, and we became friends.)

Paris reminds me of my mother. She visited me when I lived there, shortly after she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. She had her chemotherapy treatments at the American Hospital in Neuilly during the time Rock Hudson was there dying of AIDS. We had to walk through the paparazzi on our way inside. My mother was poignantly starstruck. On days when my she felt well enough she would carry the watercolors we'd bought at Sennelier and sit by the Seine just down the street from my apartment, in a narrow park lined with trees and full of interesting shadows, and she would paint.

Did I need to connect with thoughts of my mother? And of my father, who had fought in World War II and told us stories of France? Perhaps so, and I did. I thought of both my parents, who had never been to France together. It's odd the way each of them--my father had been shot down over Alsace, my mother had never been on a plane before flying to Paris to stay with me--was connected to France so definitively by flight.

I didn't only spin back into the past. Most of the time during this stay I remained present, in the actual day. I wrote at the hotel and in cafés, and I made sure to walk a few unfamiliar streets. I stopped into favorite bookstores and found others I'd never seen before. Paris is books to me--ones I've read, and some I've written. In 1985 I wrote Crazy in Love, my second novel, sitting at my desk in the cramped office under the eaves, and this year I worked on my thirty-third novel in a seventh-floor hotel room just a block away.

Love locks are everywhere. Padlocks left by people in love cram not only every inch of grate and rail on the classic spots such as the Pont des Arts, Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor, and Pont de l'Archevêché, but also random little pieces of hardware all along the river.

Did I also spend an afternoon, writing at a table in the corner of the bar at Closerie des Lilas, in an homage Islands in the Stream by Ernest Hemingway, from which my sister Maureen and I quote far too often? Yes, I did. And I called Maureen afterwards, and as I walked though the Jardin du Luxembourg she offered up lines from the book regarding that Tommy and red wine.

My first day in Paris I went to lunch, and on my last night there dinner, at Le Stresa, a favorite restaurant in the 8th Arrondissement. Owned and operated by six brothers, les Frères Faiola, it is tiny and great, and although it is Italian, it is so Paris. I loved seeing the brothers, and was touched that they remembered me, right down to the year I lived on their street. At the end of the meal I had fraises des bois. They were delicious.

And Paris is still home.

The PEN Ten with Luanne Rice

I felt honored to be interviewed by Lauren Cerand for Pen America's Pen Ten series.

- By: PEN America

- PUBLISHED ON DECEMBER 9, 2014

The PEN Ten is PEN America's weekly interview series curated by Lauren Cerand. This week Lauren talks with Luanne Rice, theNew York Timesbest-selling author of 31 novels, which have been translated into 24 languages, including The Lemon Orchard, Cloud Nine, and Dream Country.

When did being a writer begin to inform your sense of identity?

From as far back as I can remember. As a child I wrote poems about nature and stories about people with secrets. As a child I could look out my bedroom window and see the Children’s Home on top of the next hill. We went to school with kids who lived there. There was one boy I wanted us to adopt, but our family had our own sorrows, and my parents said it wasn’t possible. I remember crying that night, and instead of sleeping I wrote a story about a boy with freckles and a hole in his sweater.

Whose work would you like to steal without attribution or consequences?

The idea of stealing another's work is horrifying to me. Writing is the closest thing to sacred I know.

Where is your favorite place to write?

By a window with cats on my desk.

Have you ever been arrested? Care to discuss?

I’ve never been arrested, but as a teenager I was accused of vandalism. A state trooper came to my house late at night. It was frightening to be accused of something I hadn’t done, and to feel I wasn’t being believed.

Obsessions are influences—what are yours?

Coastal New England, factory towns, Chelsea prior to gentrification, sisters, fathers, love, immigration. I’ve gone to Ireland to stand on the docks and commune with the family ghosts. I have Mexican friends living undocumented in LA. One woman was trafficked, and she is traumatized and can’t go anywhere for help because she fears getting caught without papers, and she fears the coyote who imprisoned her will come after her or take revenge on her family.

What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

In my first novel I wrote about growing up with an alcoholic father. I had been tempted to censor myself, but somehow I didn’t. I wound up being disowned by some members of his family, and at my first-ever reading—at the New Britain Public Library, in my home town—a friend of his stood up and said he was glad my father was dead so he didn’t have to read what I’d written.

What is the responsibility of the writer?

To tell a story.

While the notion of the public intellectual has fallen out of fashion, do you believe writers have a collective purpose?

Yes, I feel it strongly. At this year’s Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Literary Festival I sat on a panel with Luis Alberto Urrea and Cristina Henriquez. It was powerful for me—they have written wonderful books about immigration, and I felt honored to join my voice with theirs. Luis is a kind of spirit guide for me. I keep his book about death on the border, The Devil’s Highway, close to me, on my desk. Before writing The Lemon Orchard, I asked him if it was okay for me to write about illegal immigration because it’s not, literally, my story. I’d never worried like this before—I’ve always written from my heart and obsessions, written what I dreamed and felt. But in this case I was writing about people crossing the border, dying in the desert or living in fear, undocumented in Boyle Heights, and it was inspired by real families and actual events. I worried that this story wasn’t mine to write. But Luis told me that not only could I write it but that I must. I felt tremendously supported.

What book would you send to the leader of a government that imprisons writers?

Freedom in Exile by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Where is the line between observation and surveillance?

Observation is gentle, surveillance is brutal.

In Praise of Recklessness: Notes on Writing

When I was little and would leave my mother's side, she would always say, "Be careful." And I was, mostly. Those words were my invisible tattoo. I paid attention to the rules. We didn't have sidewalks in our neighborhood, and when I walked my sisters to school, I made sure we stayed a safe distance off the busy road, a few feet onto the grass or around trees, out of danger. In seventh grade and through high school I attended Catholic school. One of my boldest moves was roll the waistband of my uniform skirt a few times to make it shorter than the rules--and nuns--allowed. I took care.

Even now I have to hold myself back from using those words as a mantra: be careful. I say the phrase too often to the young people in my life. If I thought my cats would heed, I would say it to them, to keep them from falling off the high, narrow beams they love to explore. In certain areas of my life, I am protective--even over-protective.

When I was little and would leave my mother's side, she would always say, "Be careful." And I was, mostly. Those words were my invisible tattoo. I paid attention to the rules. We didn't have sidewalks in our neighborhood, and when I walked my sisters to school, I made sure we stayed a safe distance off the busy road, a few feet onto the grass or around trees, out of danger. In seventh grade and through high school I attended Catholic school. One of my boldest moves was roll the waistband of my uniform skirt a few times to make it shorter than the rules--and nuns--allowed. I took care.

Even now I have to hold myself back from using those words as a mantra: be careful. I say the phrase too often to the young people in my life. If I thought my cats would heed, I would say it to them, to keep them from falling off the high, narrow beams they love to explore. In certain areas of my life, I am protective--even over-protective.

But not writing.

When it came to writing, I encourage recklessness. This comes from experience. Writing my first novel, Angels All Over Town, I drew on my life. It's fiction--not memoir, not autobiography--but emotionally my book was very close to what I knew to be true at the time I wrote it. It's a story of sisters who had considered themselves inseparable, and then things come along to separate them: mainly love and loss. They fall in love with men who don't necessarily get along; their father dies. They grow up, and it hurts. These facts mirrored reality in my life.

If I'd been careful, everyone would have gotten along. Everyone would have been nice to each other. The protagonist wouldn't have told the messy truth about her father's alcoholism. The sisters would have been chaste instead of falling dangerously in love with Australian sailors on the Newport docks. The mother would have spouted words of wisdom instead of isolating herself at her easel with watercolors and cups of milky tea.

Fiction requires bravery. Writing that novel allowed me to see my characters, those three sisters, with some measure of detachment. They didn't climb the Matterhorn or sail the Atlantic single-handed--they lived in Newport and made their way in life, and in small ways and large ways learned about their world, and about each other, and, most scarily, about themselves. They faced their father's death. They were wild. They drank, but even more, the oldest sister recognized the way their father's drinking had affected the family. I was in my twenties when I wrote that book. What did I actually know back then? More than I thought, apparently.

If you're a writer, write the deepest and truest you can. Go close to the edge. Play in traffic. Sit at your desk every morning and face the page. Write what alarms you. Don't censor yourself or worry about what your friends--or your husband, or your mother, or your high school teacher--will think. If your dreams are haunted by a terrible family secret, and you feel it's your duty to keep it under wraps, don't. Write about it. Write down every detail. Tell the secret. Write it from your heart.

You can always burn the pages, but I hope you won't.

Sometimes writers hold themselves back by comparing themselves unfavorably to their idols--or their peers, or their younger or older or imaginary better selves. This is a waste of time and spirit; it will do nothing but hold you back. All you can do is face the page. "Believe in yourself" might sound corny and New Age and dumb, but it's not. It's the way to go. If you feel called to write, then you must write. It's nice to have support and affirmation from outside, but that's not always possible or forthcoming. So you have to give it to yourself.

This doesn't mean you should consider shoddy work to be brilliant. The Rules of Grammar are not made to be broken. Read The Elements of Style by William Strunk and E. B. White. Read books you love. Read a lot. Remember that thinking about writing, dreaming about writing, talking about writing, attending workshops about writing is not the same as writing. The only way to write is to sit down and write. Write for hours every day if possible. Don't hold yourself back. Tell secrets. Make up stories. Tell the truth--or don't. Be reckless.

I dare you. There's nothing more thrilling, and I want that for you.

Excellence in Reading

Emily May Beaudry was born on November 6, 1898 in Providence, Rhode Island. She was the second oldest in a family of eight children, two of whom died young. She wore her long dark hair in braids. At school she enjoyed dipping their tips into the inkwell and writing and drawing with them. That got her into trouble, and so did fighting, which she did to protect her younger siblings from bullies.

Emily May Beaudry was born on November 6, 1898 in Providence, Rhode Island. She was the second oldest in a family of eight children, two of whom died young. She wore her long dark hair in braids. At school she enjoyed dipping their tips into the inkwell and writing and drawing with them. That got her into trouble, and so did fighting, which she did to protect her younger siblings from bullies.

The family lived in the Thornton neighborhood of Johnston, a section of Providence known for textile mills (Thornton was named after a village in England, the hometown of one of the mill owners) as well as the natural beauty of Silver Lake and Neutaconkanut Hill. Emily's grandfather's house had a basement kitchen where everyone could put on their skates and walk right outside onto the lake, and the hill was good for sledding. Emily's many aunts were known for their grace on the ice, the way they could skate the grapevine and the reel.

The entire family worked at British Hosiery, one of the local mills. Emily's mother, Gertrude, had grown up in Nottingham, England. Her parents had brought her and her brothers and sisters across the Atlantic with other mill worker families--a hundred and twenty people in all--to work at the hosiery.

In December 1884 the family crossed the North Atlantic from Liverpool on the Cunard steamship Aurania. They traveled in the cramped and difficult conditions of steerage; on that same passage, several decks up, in a different class, was Dr. Dugald Campbell, a Scottish doctor who may-or-may-not be the great-grandfather of J.K. Rowling. The ship made landfall on the eve of Christmas Eve; when Gertrude's father asked the mill owner if they could go to a Catholic Church for midnight mass, the owner was dismayed; he had assumed that, being from England, these immigrants were not Catholic.

Gertrude went on to have eight children of her own; she named her second daughter Emily, after her mother. Emily excelled in school. She was high-spirited, and teachers sometimes scolded her, but she loved school. Although she did well in all her subjects, her favorite was English. She was a great storyteller in a family who loved to tell stories; a dinner at their house would be full of laughter and interruptions, and one person jumping in to finish the story another had started. Books were expensive, and there wasn't yet a library in town, but she read everything she could at school.

When she was in eighth grade, on January 31, 1913, she won the Johnston, Rhode Island medal for "Excellence in Reading."

That was Emily's last year in school. She had to leave before ninth grade, to go to work in the mill. "At the hosiery," she would say, and never with resentment, or a sense of what might have been. She had been a smart, spirited girl, whose education was cut short. She had to help support the family. This was just how it was done; there were no expectations of finishing school. Whatever she may have hoped, whatever her secret dreams may have been, she put them aside and went to the mill every day.

Child labor was common. Long workdays--twelve to fourteen hours--were the norm. Wages were low, and the factories were loud and dangerous, with thundering machinery and poor light. The workers breathed fiber-filled air as they spun thread and wove cloth. The young millworkers perfected the art of spinning. Weaving thread instead of stories...

Emily was my grandmother. She lived with us from the time I was born, and I called her "Mimi" because I couldn't say "Emily." She told lots of stories, but they were alway full of love--about how she and her sisters Florence, Josie, and Ida would take the ferry from India Point in Providence, down Narragansett Bay. They would always intend to go out to Block Island, but they could never get past Newport--they loved it so much. They'd cram into one small room at Mrs. Richardson's boarding house, and go to Easton's Beach to meet their friends. Or she'd talk about Silver Lake, putting on skates in the basement kitchen and going out onto the ice with her aunts. And her voice would lower, telling how the Grand Trunk Railroad bought up all those houses around the lake, including her grandfather's, and knocked them down, and then the railroad never came through.

Emily was my grandmother. She lived with us from the time I was born, and I called her "Mimi" because I couldn't say "Emily." She told lots of stories, but they were alway full of love--about how she and her sisters Florence, Josie, and Ida would take the ferry from India Point in Providence, down Narragansett Bay. They would always intend to go out to Block Island, but they could never get past Newport--they loved it so much. They'd cram into one small room at Mrs. Richardson's boarding house, and go to Easton's Beach to meet their friends. Or she'd talk about Silver Lake, putting on skates in the basement kitchen and going out onto the ice with her aunts. And her voice would lower, telling how the Grand Trunk Railroad bought up all those houses around the lake, including her grandfather's, and knocked them down, and then the railroad never came through.

I never heard her complain about the mill, or about having to leave school. I never heard her speak of regret. But she kept her medal in her bureau drawer, in the original box. She would sometimes show me. Other times I would sneak into her room and open the drawer and look at her medal, and I'd wonder how it must have felt to be honored for reading, to be an eighth grade scholar, and then to be sent to work at a factory.

Today is her birthday. Happy birthday, Mim...

I don't have any photos of her as a child, so I sought out pictures of girls with braids who worked in textile mills around the turn of the last century. I am posting two from this site, which contains old photos of child labor between 1908 and 1924. I love these girls, they could so easily be Mim and her sisters.

I don't have any photos of her as a child, so I sought out pictures of girls with braids who worked in textile mills around the turn of the last century. I am posting two from this site, which contains old photos of child labor between 1908 and 1924. I love these girls, they could so easily be Mim and her sisters.

Connecticut College Magazine Photo Shoot

I was so honored to learn Connecticut College wanted a profile of me for CC Magazine. Amy Martin, the magazine's wonderful editor, made it all happen. Ben Parent, art director, and Bob Handleman, photographer, and Bob's assistant--and fine photographer in her own right--Lindsey Platek came over one August day and we had a great time on the photo shoot. Ben Parent is a real visionary, and Bob is a great artist, and they made my little cottage at Hubbard's Point look so magical. Not only that, Ben provided a great soundtrack, thanks to his band Rivergods. Here are some photos from that day...

I was so honored to learn Connecticut College wanted a profile of me for CC Magazine. Amy Martin, the magazine's wonderful editor, made it all happen. Ben Parent, art director, and Bob Handleman, photographer, and Bob's assistant--and fine photographer in her own right--Lindsey Platek came over one August day and we had a great time on the photo shoot. Ben Parent is a real visionary, and Bob is a great artist, and they made my little cottage at Hubbard's Point look so magical. Not only that, Ben provided a great soundtrack, thanks to his band Rivergods. Here are some photos from that day...

There and Not There

Late October, looking west from Chelsea, tonight's sunset is particularly iridescent. I see the sky, and the Hudson River, and planes in their landing pattern at Newark Airport, and Dan Flavin untitled at the Dia Art Foundation, and I look through the stories of the new building and pretend it's not there, and I think of this poem, one of my favorites.

Late October, looking west from Chelsea, tonight's sunset is particularly iridescent. I see the sky, and the Hudson River, and planes in their landing pattern at Newark Airport, and Dan Flavin untitled at the Dia Art Foundation, and I look through the stories of the new building and pretend it's not there, and I think of this poem, one of my favorites.

Evensong by Peter Kane Dufault

Last night when the sun went down and the light lifted up— it was levered off the last high land westward through tier after tier of cirrus and cumulus cloud, all the way to the zenith— such a finale of auroral cold fire no one could speak here. We stood like pillars of salt looking after it a long while till it faded into grey and dark-grey. Oh, how do we survive it, how do we survive, when more than we dared dream of is given for no reason, and for no reason taken away.

(From On Balance-Selected Poems 1978)

Strange Gifts and Surprises

Fall in New York is an exciting time. It feels like the best of what you remember about going back to school--so many thrilling new subjects to discover and things to learn, while outside the weather is crisp and the leaves are turning. Theater can be wild at any time of year, but in October many new plays have arrived, and are in previews, and there is tremendous energy and excitement in the air. This is a blog about a play, but it's also about friends. On Sunday I attended a preview of Sticks and Bones by David Rabe. It won the Tony award in 1972; my mentor Brendan Gill gave it a rave review in The New Yorker on March 11, 1972. This is the play's first production since then. Directed by Scott Elliott, it stars Bill Pullman, Holly Hunter, Richard Chamberlain, Ben Schnetzer, Raviv Ullman, Nadia Gan, and Morocco Omari.

The play tells the story of an American family in the aftermath of war, when their oldest son returns home from Vietnam. It did what great theater can do. It changed me. It ripped me apart and put me together differently. After it was over I saw friends in the lobby, but we couldn't speak. I think we babbled something, but speechlessness had taken hold. I know I wasn't in my body. I was floating somewhere above this earthly plane where genius art and poetry and existential sorrow exist, where I lived for the duration of the play and quite a long time afterwards.

The timing of my speechlessness was unfortunate, because I found myself in a room with friends both old and new. Bill Pullman and Holly Hunter first acted together in Crazy in Love, the first movie made from a novel of mine, and I got to know them while filming in and around Seattle. Their performances in Sticks and Bones are breathtaking.

Bill inhabits his character with such ferocity, such wrecking ball swings of hope, shame, love, hate, the dynamics of a particular moment in the life of a man trying to balance suburban fatherhood with his own met-and-unmet expectations of himself, I felt completely rattled, illuminated, reminded, destroyed, and turned inside out. It is a brilliant, shocking performance. Holly's character is so tender, vulnerable, grasping onto faith as every observable detail and every unseen nuance at home seems to shift and attack the life she's always counted on, and she nails it in her inimitable and savage Hunter way. Between the two of them, we have a fever dream of an acting duo that will raise your temperature and make you delirious on your way to a greater truth.

Beth Henley--with whom I was fortunate enough to work on Motherhood Out Loud (both Holly and Bill have acted in several of Beth's plays, Bill most recently getting a Drama Desk nomination for his portrayal of Fred in The Jacksonian) and Carol Kane, had come to the play, and I met up with them afterwards. And then Bill, Holly, the rest of the cast, director Scott Elliott, and David Rabe came out to join us, and I could barely speak because I was still living in the world of the play, the emotions it had brought forth, and the seriously intense physical sensations of a wild ride.

In my post-play near-hallucinogenic state, I did greatly enjoy meeting Ben Schnetzer and Raviv Ullman. Ben's character David is compelling, tragic, and full of secrets and all that is wrenching about war. Raviv's character Rick seems to be holding the family together, until we realize he is every bit as affected as his parents and brother; his guitar playing provides a mystically tranquil and deceptively reassuring backdrop to one of the play's most devastating scenes.

In Sticks and Bones, David Rabe writes deeply of a time and family, a way of being that felt so familiar to me, having grown up during Vietnam. The play caught so many details with such specific and almost magnified realism, yet managed to transcend everything actual--everything "real"--and somehow make it truer than true, realer than real.

I hope you all will see Sticks and Bones--if you're coming to New York and have time to see just one play this season, I encourage you to make sure this is the one. It will shake you up and make you think and then make you stop thinking in the most thrilling of ways.

In a fun and somewhat surreal aside, earlier this fall I took a bus ride from Port Authority to Montclair NJ, with Bill, Holly, David, and Rachel, to see Bill's lovely and talented wife Tamara dance in Liz Lerman's gorgeous Healing Wars which, like Sticks and Bones, is about the trauma and effects of war. There we all were, on the bus, with the crazy lights of the Lincoln Tunnel flashing through the bus windows, and then that heartbreaking view of the New York skyline, and then in the distance a crescent moon balanced over the Pulaski Skyway (which has always reminded me of a crouching panther) as we drove through the swamps of Jersey, on the way to see a great performance. Life can be full of strange and wonderful gifts and surprises.

The Tiny Terrace in the Sky

This morning the tiny terrace in the sky was a haven for golden crowned kinglets.

This morning the tiny terrace in the sky was a haven for golden crowned kinglets.

Every fall migratory birds fly south from their breeding grounds in the Canadian forests on their way to the tropics, and large numbers stop over in New York City. Central Park is one big concentrated stretch of green from the air, and it attracts the migrants, provides a place to rest and forage before continuing the journey.

The tiny terrace is west and south of Central Park and has just one birch tree, one black pine, a hedge of ivy and Manhattan euonymus, and a small herb garden, but I am so glad to see the birds have found it.

There is so much about New York that I love, but sometimes I can feel nature-deprived. It is always possible to hike up to Central Park, or along the river in Hudson River Park, or Forest Park or Alley Pond in Queens, or Floyd Bennett Field or Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, or Van Cortlandt Park or Pelham Bay in the Bronx, or the magical Staten Island Greenbelt, but there's nothing like sitting at one's desk, glancing up, and seeing a bird in a tree just outside the window.

I'm not the only one who likes watching birds; to keep the birds safe from Emelina, and to protect her from falling off the terrace, I make sure she stays inside with Green Tara.

Birds face enough dangers on their migrations, and New York provides special challenges. They crash into windows on skyscrapers; it's not uncommon, in the morning, to walk by tall buildings and find dead or injured birds. Light can also be a magnet. New York City Audubon and Project Safe Flight are working to improve things.

Creatures migrate. It's how they survive. Humans, too.

Meanwhile, up here, feeling grateful for the delicate beauty of birds and sky.

Talking Bruce Springsteen

Today at 4 pm I'll be the Guest DJ on SiriusXM's E Street Radio, talking about Bruce Springsteen and playing ten of my favorite songs of his. I am inspired by Bruce's music. From the beginning I was captivated by his passion for storytelling, the way he focuses in on the places and people he loves most, the issues he cares about, the underdog and the downtrodden, people's stories that otherwise might not be heard. He's been a voice for migrants, the deeply human story of immigration, and that touches me so much. I love his song Matamoros Banks, which he introduces with these words:

"Each year many die crossing the deserts, mountains, and rivers of our southern border in search of a better life. Here I follow the journey backwards, from the body at the river bottom, to the man walking across the desert towards the banks of the Rio Grande."

There is so much to say, and I make a start during my hour on E Street. I hope you'll join me.

the songs:

~matamoros banks live from devils and dust tour, along with bruce's psa about immigration.

~land of hopes and dreams (from live in nyc)

~ghost of tom joad (acoustic)

~my city of ruins from the concert for new york city after 9/11

~born to run

~incident on 57th st from the june 22 2000 show including bruce's psa for new york cares.

~youngstown

~badlands from the october 1, 2004 vfc concert in philadelphia

~if i should fall behind (live in nyc)

~the river, if enough time the live version with bruce's intro from live/75-85

Lanterns in the Night

On October 18th Rachel Hartwig went to the Mojave Desert with her mother to participate in the RiSE Lantern Festival 2014. She had been telling me about it, and I knew she was excited to go, and she told me she was going to release a lantern in my name, but I honestly had no idea how beautiful and meaningful it was until after she sent me this video (notice the words at the end.)

On October 18th Rachel Hartwig went to the Mojave Desert with her mother to participate in the RiSE Lantern Festival 2014. She had been telling me about it, and I knew she was excited to go, and she told me she was going to release a lantern in my name, but I honestly had no idea how beautiful and meaningful it was until after she sent me this video (notice the words at the end.)

Rachel is a reader who has become a friend. I first met her several years ago when she came to my reading at Warwick's in San Diego. She and her husband Mike had driven all the way from Las Vegas. I thought that was pretty incredible. She made the same trip this year, only she brought a cheesecake for everyone who showed up at the bookstore, packed it in ice to keep it cold, and served it to the gathering. The cake was delicious.

No writer expects anything from a reader; we only hope you'll enjoy our books. But to think of Rachel going to the Mojave Desert to release a lantern in my name, with all the hopes and dreams and spiritual meaning it represents, is very humbling. She also wrote this beautiful blog post. I feel so honored and grateful.

Maisie and Tim: a Love Story

maisie

I wouldn't exactly call Maisie a "problem cat" (there-are-no-bad-cats) but ever since she was a kitten, she has had a certain personality: contrary, cantankerous, particular in whom she allows to approach (no one.) She was a rescue cat who had lived through the tragic circumstances of losing her mother too young and being left alone, sick, and flea-ridden until a kind vet in Old Lyme, Connecticut took her in. I and the old girls--Maggie and Mae Mae--adopted her. Time passed. We lived in New York, and for a while in Malibu. The dynamic of those three cats was of love, but separation. Each kept to herself. There were occasional stealth attacks--Maisie, stalking the others like a wild cat, pouncing, letting out lion-sounding snarls. Maggie would sit closest to me, on my desk while I wrote, and after she died, Mae Mae nuzzled her way in. After Mae Mae died, I waited for Maisie to claim her spot on the desk, but she never did. She was a loner cat, preferring to sit under chairs rather than on them, staring at me with her green eyes, coming out to be fed, but rarely petted.

Then along came Tim and Emelina. Like Maisie, they'd been rescued from life on the streets, and we adopted them from West Chelsea Vets.

Tim and Emelina at West Chelsea Veterinary, the day we adopted them.

The twins moved in, and I was a little worried that Maisie, although now fifteen and less angry, would intimidate them--maybe even attack them. They had such sweet personalities, loving to be held and petted, and often cuddling up with each other. I watched Maisie carefully, ready to pull her away from the kittens if I saw too aggressive a swat.

Emelina took the hint and stayed away from her. She made herself at home and kept her distance.

Emelina

But not Tim. He loved Maisie from the beginning and was determined to make friends. His initial approach, however, didn't go very well.

But he's a brave and persistent cat, named for surfer Tim West, so he stayed close and watched.

And watched.

And watched.

And watched some more.

Maisie noticed, and after a while she began to semi-tolerate his attention, sometimes throwing him a glance.

After a while this happened:

Then this:

They made friends.

Tim is also very sweet with Emelina, but this story is about him and Maisie. Emelina does, occasionally, hang out with them.

But mostly, if Maisie lets anyone close, it's Tim.

He taught her about love. She's almost a different cat. Amazing that love can do that.